Written by Lee Arden

As a Dick’s collective member whose life revolves substantially around zines, I am here to respectfully but insistently ask that you consider becoming a weird little freak about zines too.

Zines embody a do-it-yourself/do-it-together ethos of embracing imperfection, bypassing gatekeepers, and demanding that the world acknowledge your silly little book whether they like it or not. As a group of people who were handed certain bodies and types of clothes and places in the world and decided “no thanks 🙂 i’m gonna do something different,” trans people have all the risk factors for making and enjoying zines.

AND, there are a lot of great zines available to borrow from Dick’s! The inclusion of zines in libraries is a great boon for readers, because zines are often printed in small runs and not available widely or for a long time. Some of the zines we have are hard to find, and I feel so lucky to be able to borrow them and to help make them available to you.

Today I’d like to tell you about three zines in the Dick’s catalogue that hold a special place in my heart.

Der Eydes

From Montreal artist Cesario Lavery, Der Eydes is a serialized comic in two volumes (so far) about the unexpected ways we can find ourselves connected to histories, families, and stories.

Walking home from work one night, Lavery finds an old book in a free library. On taking it home, he discovers that the book is filled with ephemera belonging to its original owner, Chaim F. Shatan. Looking into Shatan’s life leads Lavery to connect with some of both Shatan’s family members and his own.

Risograph-printed in blue and pink, Der Eydes is a lively, moving story of Montreal past and present, and the ways they intertwine, and of Jewish diaspora and resistance. It’s a story about falling head-over-heels into an unexpected connection with someone you’ve never met, and chasing that connection down, wondering at how surprising and happenstance life can be. It points to the ways that history across diaspora and displacement will always be fragmented, and the bittersweet joy of putting some of those fragments together while knowing that others will always be lost.

Der Eydes is unfortunately not currently in print or for sale, although people are working on that (👀). For that reason, it’s part of our non-circulating collection, which means you can’t borrow it, but we will often bring it with us to events for you to browse. But I wanted to mention it anyways because it’s a really special one– all the more reason to come out to one of our events!

Der Eydes Vol. 1 at Dick’s; Der Eydes Vol. 2 at Dick’s

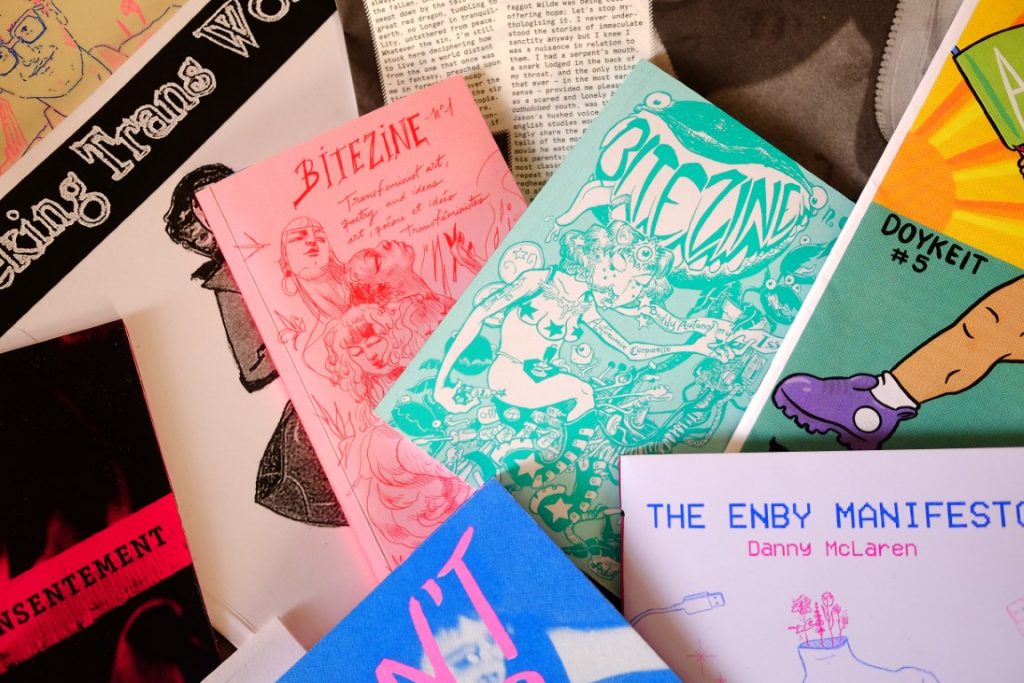

BITEZINE

Bitezine is one of the zines I’ve been most excited to read in the past couple of years. First of all, it’s beautiful: tiny, perfect-bound pocketbooks, with gorgeous cover art, and printed from cover to cover in one colour per issue, creating the feeling of something intimate and precious.

But inside, the zine is expansive, filled with a rich variety of nonfiction, poetry, visual art, and interviews from emerging (and occasionally well-known) transfeminine writers, in both French and English, sometimes sliding between the two in one piece d’une manière tellement montréalaise.

Bitezine is published by TRAPS, the transfeminist “autonomous collective of mutual aid, sisterhood, and political action”, whose projects include a mutual aid fund and an active roster of social events by and for transfemme/transmisogyny-affected people in Montréal. Money made from bitezine also helps fund this work.

The first issue includes memories of a friend who has died, an essay about being trans in prison, and a blackout poem made from the DSM criteria for gender dysphoria. The views on transfemininity and transfeminism are expansive in genre and feeling and style: it doesn’t ask that you think or feel any one type of way, but instead presents you with a whole ecosystem of ideas and lineages and possibilities.

While issue 1 (2023) was more general, issue 2 (2024) has a focus specifically on bodily autonomy. Issue 2 was originally conceived as a guide to DIY HRT, but the editors decided to spin off that project and (hopefully!) put it out later, while publishing bitezine #2 as, rather than a handbook, a collection of art and recollections about the many ways to have and think about bodies. It’s about medical transition, sure, but also rehab, magic, and growing up in a lesbian separatist commune. And it also has that famous Sybil Lamb story about DIY orchiectomy, and that in itself is worth the price of admission.

Bitezine is published by Coop de solidarité Agenda, which also operated the short-lived but wonderful Librairie Agenda. They write that they “aim to build material resilience for transmisogyny-affected people by providing wages and financially supporting authors and initiatives through books and zines sales.”

Bitezine is now up to Volume 3, and I bet after you borrow the first two issues from us, you’ll want to pick up a copy of Vol. 3, which is on the theme of “Romantiques et renouveau”.

Bitezine Vol. 1 at Dick’s; Bitezine Vol. 2 at Dick’s

Fucking Trans Women

I had to include Mira Bellwether’s Fucking Trans Women is one of my favourite zines of all time, and really represents to me the best of what zines can be and do. I strongly recommend it for anyone who fucks, or is, trans women.

This zine is probably most known for naming and popularizing muffing, the penetration of the inguinal canals of someone who has or has had testicles. This is in itself a vital contribution to the world, but I also really love the ways, more broadly, that FTW encourages its readers to think of their bodies and their lovers’ bodies with flexibility and curiosity, outside of the usual social scripts that govern the way we think of what different body parts are for.

Bellwether writes a lot in the zine about choosing not to assume that someone whose penis isn’t hard isn’t turned on or enjoying sex, and that there are a lot of fun, hot ways to enjoy a soft penis (I’ll note that I am following the zine’s lead in the anatomical terminology used.) She also writes about not believing that “all there is to good sex is good communication”, and that skills and knowledge actually often matter quite a lot, which was one thing that really stuck with me from my initial reading of this zine.

From about 2012 to 2016, I ran a zine distro in Ottawa. In 2015, I bought an optimistic 25 copies of FTW from Mira, and when I wound the distro up, I had a bunch left over. I carried a bag of them around in my backpack for a while, and put one into every Little Free Library I came across. I hope some of them found good homes.

Mira died of a stroke related to lung cancer, in December 2022, at only 40 years old. Writing about her, and FTW, after Bellwether’s death, Sloane Holzer wrote,

“Throughout the zine, Bellwether stressed that this work was only a starting point. Despite multiple calls in the work for submissions and reader contributions, very few came. According to multiple people who knew Mira, both at the time of FTW’s publication and in the decade plus since, this was the response to the work that made her the most incensed. It seemed to be easier for the zine’s readership to treat the work as gospel than it was to do the kind of messy reflection she had done, the kind of work she was daring her audience to do.”

I relate very strongly to this frustration, and reading about someone I admire so much articulating the same experience made me feel a strong sense of kinship with her. If you like zines it is, unfortunately, your duty to make zines. If you appreciate someone’s scrappy determination to tell their story, and the work that results, I actually believe you’re at least a little obligated to increase the volume of idiosyncratic art in the world.

When you search “zine” in the Dick’s catalogue, you’ll find a wealth of cool stuff you can borrow. You should borrow some zines! Even more than other media, I think zines really want to be shared and passed from hand to hand.

When we table at events, Dick’s also often sells zines to raise money for causes close to our hearts, such as the Sudan Solidarity Collective and Mubaadarat, a collective supporting LGBT+ people in Montreal from Arabic-speaking regions.

If you’re interested in donating your zines to the library, either to become part of its collection, or for us to sell to raise money, please get in touch at dickslendinglibary [at] gmail [dot] com. We’d love to hear from you, and we can’t wait to see what you make.

Dlog is the Dick’s Lending Library blog. We welcome submissions of book reviews and reactions, guides like this one, that survey a form, genre, or theme of materials in the Dick’s collection, or other topics relevant to trans, non-binary, Two Spirit, and gender non-conforming readers and writers and organizers in Tio’tia:ke/Mooniyang/Montreal. Please get in touch at editorial [at] dickslendinglibrary [dot] com if you’d like to get involved.